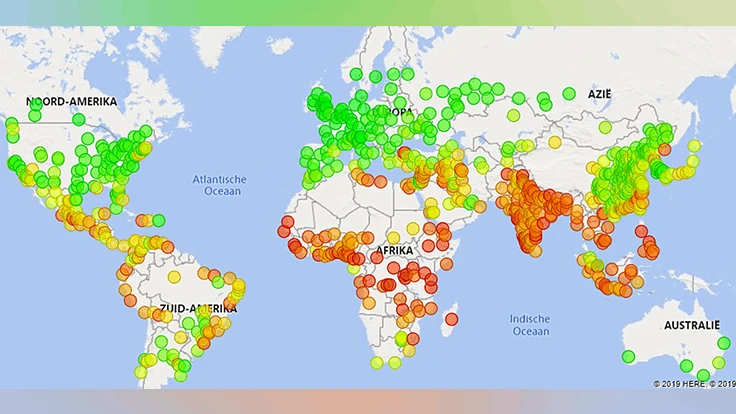

Map courtesy of Peter Ravensbergen

Wageningen University & Research has released a new study on food security and healthy lifestyle in 850 cities across the world. Nine Canadian and 77 American cities are included. A corresponding chart from WUR of North America’s 25 largest cities includes 16 U.S. cities and two Canadian cities. Out of these, food security is high in Montreal and Toronto and is average or above in 12 U.S. cities. However, it is below average in four of the largest U.S. cities: New York-Newark, Miami, Boston and Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana.

The research provides a snapshot into the global food market, says Peter Ravensbergen, business developer at WUR and horticulture engineer. Cities are given one out of nine scores from “very low” to “very high,” on five elements: availability, food risk, healthy lifestyle, accessibility and affordability. Together, these elements determine an overall rating.

How CEA can improve food urban security

As more people, young people in particular, move from rural to urban areas, the demand for fresh and healthy food is growing, Ravensbergen says. Controlled environment agriculture can help meet these food needs in North America’s cities.

“Indoor production we define as ‘greenhouse horizontal’ and ‘greenhouse vertical,’” Ravensbergen says. “Apart from this, we have open field. In general, it can be said that open field, even if it is accessible and affordable, is losing ground to indoor. Production closer to consumption is growing.”

But growing within a city might not always be the best way to supply product to it, he says. High land prices and taxes, such as real estate taxes, might not allow for economic viability. In addition, costs are high in city centers for logistics of waste materials, sales and supply goods.

Vertical farms, specifically, produce a broader assortment of produce than greenhouses. In addition, vertical farming involves high investments, and costs of labor and electricity are high. “Therefore logistical costs will be high for last mile distribution to distribute the produce to further areas,” Ravensbergen says.

“[Research shows] that high-tech vertical farming will be located much more near to distribution centers, or near to trade centers, a little bit outside of the city,” Ravensbergen says.

Growers can help feed cities while saving money and improving sustainability by forming circular economies with other industries and growers, and with municipalities, he says. This can help them improve the efficiency of their logistics, energy and water use and waste management.

Roughly 600 greenhouses have teamed up in Westland, a region in the western Netherlands, to grow in about 9,884 acres of greenhouse space. The food grown there and in five other Greenport regions, including tomatoes, hot peppers and strawberries, feed more than 30 million people within a 200-mile radius, Ravensbergen says. For the Westland energy-saving project Trias Westland, 49 companies have started digging up warm water from 2.5 miles underground, according to westlandhortibusiness.com.

Other food security factors

Food security overall differs between the 25 largest cities in North America and Europe, with European cities possessing nine “very high” scores and those in North America having none. Part of the reason for this is the wealth gap in the United States, which is higher than in most European countries, according to the Credit Suisse Research Institute. (WUR measured wealth disparities on country levels.) Another reason for differences is high body mass index (also measured at country levels) in the U.S., which shows that U.S. diets are generally worse than Europeans’.

Ravensbergen notes that many cities have gaps in food security between neighborhoods that are not reflected in all of WUR’s overall city ratings.

Across the United States, there is a correlation between age differences and diet. Americans between ninth grade and age 24, for instance, eat fewer fruits and vegetables than older Americans, according to the CDC. Fresh fruit and vegetable consumption among young people in Europe is also decreasing, Ravensbergen says.

Due to a demand that is not increasing in the United States and Europe, plus the specialization and economies of scale involved in greenhouse production, Ravensbergen says, U.S. and European markets may face market saturation with certain crops.

“If we are able to turn that around by awareness — education — these types of things [so] that people are maybe willing to try and eat more fresh vegetables, then the point of saturation can be extended every time,” he says.

Explore the December 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Produce Grower

- TIPA Compostable Packaging acquires paper-based packaging company SEALPAP

- Divert, Inc. and General Produce partner to transform non-donatable food into Renewable Energy, Soil Amendment

- [WATCH] Sustainability through the value chain

- Growing leadership

- In control

- The Growth Industry Episode 8: From NFL guard to expert gardener with Chuck Hutchison

- 2025 in review

- WUR extends Gerben Messelink’s professorship in biological pest control in partnership with Biobest and Interpolis