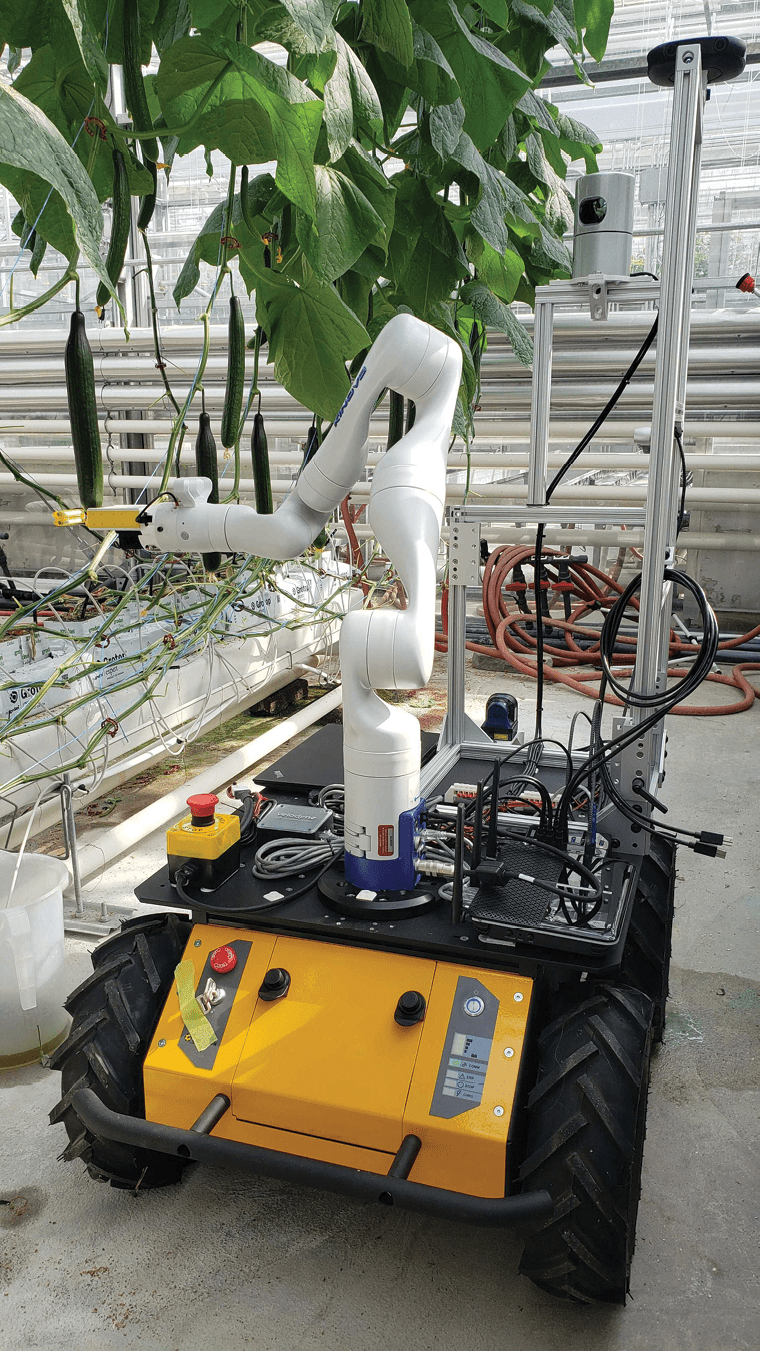

But what if there was another option for growers? After all, we’re over 20% of the way through the 21st century. Growers shouldn’t be restricted by how many people want to work for them. Brian Lynch and his team at Vineland Research are working to give growers more options by developing a robot that can harvest cucumbers.

Coming from a background in aerospace engineering, which lead to work in robotics and mining on Mars before landing in the field of autonomous robots, Lynch is a robotics research scientist at Vineland Research and Innovation Centre in Ontario, Canada, where he’s working on developing a robot that can harvest cucumbers in greenhouses.

Help wanted, humans not required

Naturally, the industry-wide labor shortage has created a sense of urgency, for businesses in other industries, to adopt automation projects like Lynch’s, which he says has made some companies more interested in working with Vineland, as they need to fill the gaps in their operations.

On top of the labor shortage, there is the issue of growers having to pay a great deal of money for what labor they can secure, as well as increases in minimum wage in some areas. These increased expenses combined with the labor shortage are incentivizing growers to look to automation.

However, Lynch believes that growers will always have to shell out some money for human labor. “There are plenty of tasks where it just would not make sense to have a robot do it,” Lynch says. Be it because the task is too complicated or such a robot would be too expensive or too slow, there are some things that humans will always have to do.

Cucumber challenges

Unfortunately for growers desperate to replace their “Help wanted” signs with robots, there are some challenges to the development of this robotic harvester.

Although Lynch says that “the two biggest challenges are speed and accuracy, or rather the success rate of this system,” there’s another complicating factor: money.

“The big, overarching challenge is to find a solution that is faster and successful in terms of how many pieces of fruit it’s actually getting versus how many you want to get,” Lynch says, “and to do that with a price tag on the robot that’s affordable.” And that’s the tricky part. It’s one thing to create the best piece of technology you can. It’s another to create the best piece of technology you can and make it affordable.

“I could throw lots of different technologies at this [speed and accuracy] problem and probably find a very easy way to solve it,” Lynch says, “but you’d end up with a robot that would cost $10 million.” And nobody wants that.

An additional challenge is how greenhouse environments can be relatively unpredictable, Lynch says. While “a greenhouse or an orchard is more structured than just going out to a forest or jungle, it’s still not the same as a controlled environment like a factory assembly line.” So, Lynch says, there are some elements of unpredictability, including things like changes in lighting conditions and changes in the plants themselves as they grow and need to be moved or repotted.

Another problem that working in a greenhouse presents is how fragile produce is, “compared to the rest of robotic applications.” No produce that a robot is picking is going to be as sturdy as the steel that the robot is made from, so the robotic harvester “can’t just grab onto it as hard as possible, which is often what you really care about with robotics in the factory setting … you just want to hold onto it.”

When you have a robot that’s handling produce, it has to be gentle, because it can damage the produce and make it unsellable. This danger is something that Lynch and his team have to keep in mind when designing their robot. When he worked on mining robotics, Lynch didn’t have to address this problem, since everything those mining robots needed to handle was solid and had to be gripped onto as hard as possible.

However, Lynch and his team minimize this fragility problem with their crop of choice: cucumbers. Compared to crops like tomatoes, strawberries or raspberries, cucumbers are much sturdier and therefore easier for a robot to manipulate. Of course, Lynch notes, cucumbers still aren’t as hard as the steel that many robots are made from, but at least they’re sturdier than other crops and won’t be smushed as easily, since, as Lynch says, “You want the food processors to handle making the relish. You don’t have to do it for them.”

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the March 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Produce Grower

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- PG CEA HERB Part 2: Analyzing basil nutrient disorders

- University of Evansville launches 'We Grow Aces!' to tackle food insecurity with anu, eko Solutions

- LettUs Grow, KG Systems partner on Advanced Aeroponics technology

- Find out what's in FMI's Power of Produce 2025 report

- The Growth Industry Episode 2: Emily Showalter on how Willoway Nurseries transformed its business

- 80 Acres Farms expands to Georgia, Texas and Colorado

- How BrightFarms quadrupled capacity in six months