Nick Brusatore’s relationship with vertical farming and strawberry growing goes back to 1999.

A machinist by education and trade, the 55-year-old Canadian started designing different growing systems in 1999 and filed for his first patent the following year.

“They were for rotated gardens designed to create microgravity for growing in space, and collapsible vertical towers where you push a button that collapses and goes up like a slinky,” he says of his early designs.

Brusatore, before going all-in on farming, was doing design projects for movies and other machinery-related products while, at the same time, playing around with different vertical farming designs, calling it a “passion.”

“It stuck,” he says, “and just as society was starting to think about dealing with all of its issues. People ask where I went to school and what kind of degree I got, and I say, ‘I’ve got 23 years and millions of dollars under my belt of what not to do.’ That’s where my experience came from.”

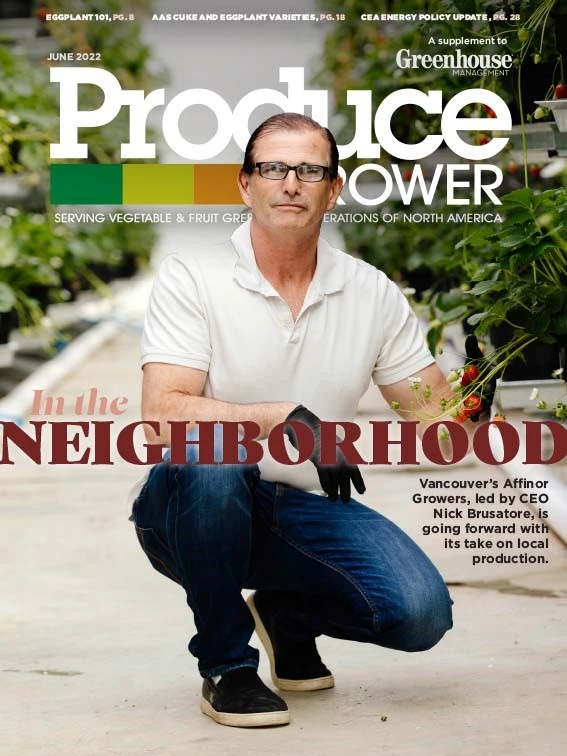

Today, based out of Vancouver, Brusatore runs Affinor Growers, a growing operation that shipped its third order of strawberries this March to retail, with more to come. Grown in a 12,000 square foot greenhouse from seedlings over the winter of 2022 in patented vertical rotating tours, the company has plans to also grow leafy greens and spinach, but the focus for now is on berries.

“It works. It makes sense,” he says. “We’re on the shelves with strawberries.”

Finding farming

Brusatore says what drew him into farming in the first place was a belief in its potential to fill an important need as the world evolved.

“The need for it [drew me in],” he says. “Having children, and having grandchildren now, and seeing the demand hit warp speed, it drew me in. And as you get older, you care more about these things.

“When you’re young, you care about making money and you’re having a good time designing [things]. But as you get older, it becomes more about the fundamentals of what we need on the planet for humanity. And that’s where I’m headed now at 55 years old.”

Back in 2000, he says he also was involved in the cannabis industry, developing a product for Canadians to grow cannabis at home. When he looks at the industry at that time, he says the space was largely wide-open and not developing commercially in the way it has now.

Between his first designs and his current ones, Brusatore says he worked on and tried out several different methods, ranging from early aeroponics to soil remediation in more traditional greenhouses, and everything in between. All of those experiences not only reinforced his belief in indoor agriculture, but also in what kind of model he would want to pursue.

“I’m designing what I need that will work,” he says. “I’m done making things that are too wild and too intricate and too automated. We don’t need that. We are just going to mass produce and kick butt, because it works.”

“All of the years of evolutionary knowledge have built up and say this: You can do it other ways, but the economics says this works and the product backs this up.”

Specifically on economics, Brusatore looks at a few key costs, notably hydro, energy and labor, vs. potential profitability of crops in affirming that Affinor’s business model works. He, for instance, can’t imagine trying to mass produce greens in a market like California where costs are higher.

As a company, Affinor Growers actually used to be a mining company called Affinor Resources that Brusatore took over in a public hostile takeover in 2012 (notably, Affinor is a publicly traded company).

“We’re working on getting the prices down,” he says. “And I’ve learned a lot personally from working with the experts we have. We have a team that is the evolved difference.”

As for interest in cannabis now, Brusatore says Affinor won’t venture into cannabis production due to what he sees as bureaucratic issues in the system, as well as the desire to attract financers who actually believe in the long-term potential of food production. In short, Brusatore believes that, over time, more people will want greenhouse-grown produce than cannabis.

“I’ll sell a turn-key solution to someone else to grow cannabis and it will be amazing,” he says, “but we will not touch it. We will not be in the cannabis space in Canada or the U.S.”

The berry growing process

The key to Affinor’s model is its technology. Energy is provided by solar panels and the company is looking at recycling rainwater and other sustainable energy measures for future projects.

Inside, the growing model is centered around four-level rotating towers that Brusatore says are planted into the ground “like trees.”

A key feature of the towers is that they are space-saving, with the company growing 20,000 plants in a 7,000 square-foot greenhouse. By Brusatore’s estimation, they get about 10 times more plants than a traditional greenhouse setup. The rotating towers also make operations easier, making unloading and loading easier for workers. Bees are used for pollination.

“We’re doing three acres of strawberries year-round,” says Brusatore. “That’s a big difference. So, in December, we have product to ship at the same time that the berries are coming up from Mexico and California, and they are terrible. No disrespect. That product can be beautiful, but they have to pick at a certain [time] of the year. And before, we had to deal with that to get strawberries. It’s that simple. They are doing their best, but unfortunately, the quality isn’t holding up.”

As for the harvesting process, Affinor’s model is based on delivering product to store shelves, at optimal freshness. Each morning at 6 a.m., the berries — branded as ‘Delizzimo’ — are pre-cooled via greenhouse-wide environmental controls. When they are picked later in the morning, they are then stored in a cooler for further temperature control. and From the time they are picked, they are on the shelf for eight hours at most. Shipping logistics are handled by a Vancouver-based company called Berrymobile, which specializes in connecting local growers to local retailers to strengthen the local food supply chain.

“Fresh-picked, pre-cooled on the vine strawberries — these are the best strawberries you can possibly get into consumer’s hands,” Brusatore says of the reason they aim to ship same-day in the greater Vancouver area. The plan is also to keep production local so if someone buys their product, they know explicitly that it was produced locally.

“I’m not going to grow so much that I have to ship to Alberta,” he says. “No — we’re just going to build another facility in Alberta and then Saskatchewan and serve those markets. That guarantees the consumer the best quality product possible without having to grow the product in their own backyard.”

Opportunities to come

As Affinor matures as a company and begins shipping more berries, Brusatore already has plans for the next expansion plans. The company’s next greenhouse — dubbed The Atlantis, a 12,000 square foot facility in Vancouver — is the most crucial component to the company’s plans.

Another component of that plan is selling the towers as a turn-key solution to interested growers. He says he won’t sell the technology outright, but instead sell the towers to a party that’s looking to start their own growing business but lacks the infrastructure to do so. As part of the business plan, Brusatore is getting back to his machinist roots and is working on scaling the towers up for mass production. He also says they’ll be able to be eight levels high instead of the current four.

“They aren’t for sale [as components],” he says. “They are only sold as a complete, full-blown greenhouse system from Affinor.” There are also possible plans to sell the towers to growers in warmer markets like California or Florida where they could grow outside while reducing some of the input costs.

For the company’s own growing plans, Brusatore says they have already filed patents for technology to grow different crops in the system, namely romaine lettuce, kale and spinach. The model for those crops is fairly similar to strawberries, with some tweaks to fit the specific need of those crops. And compared to strawberries — a crop that Brusatore calls “a tough nut to crack” in a controlled environment — Brusatore says those crops should be easier to grow.

“It’s about the ease of maintenance, the ease of growing and the abundance of square footage,” again noting that the modular towers unlock everything Affinor does now and wants to do in the future.

There’s also the financial part of it all. In April, Affinor had potential investors visit the team in Vancouver to get a look at the technology up close.

“Capital loves all the fancy numbers and pictures,” Brusatore says. “But I need them to get on the plane, come here, have a strawberry and talk to me face-to-face. The serious ones get on a plane and get here ASAP. And I’m clear of what I need. We’re sold out. You can talk to our retailers, our wholesalers, whoever the hell they want, about what we do. And they can see the quality up close. And if you can deliver a fresh strawberry to market every day, you win.”

There’s also the fact that the company is publicly traded to consider. Brusatore says it does offer the advantage of being able to publicize what the company is doing more easily and tap into public markets to raise money. The hope is that they are able to raise money fairly quickly in the near future and accelerate growth as a result. He says being a private company makes it harder to raise capital.

“I’ve been at this a long time,” he says, “and I want the world to know what we are about, soon.”All of that considered, Brusatore feels he’s spent his entire career working towards this moment. It’s been over 20 years of learning and growing, but perhaps it all happened for a reason.

“Just because you think you’re in vertical farming doesn’t mean you’re going to make a lot of money,” he says. “It means you better get it right or you’re going to fail.”

Explore the June 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Produce Grower

- University of Evansville launches 'We Grow Aces!' to tackle food insecurity with anu, eko Solutions

- LettUs Grow, KG Systems partner on Advanced Aeroponics technology

- Find out what's in FMI's Power of Produce 2025 report

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- The Growth Industry Episode 2: Emily Showalter on how Willoway Nurseries transformed its business

- 80 Acres Farms expands to Georgia, Texas and Colorado

- How BrightFarms quadrupled capacity in six months

- Oasis Grower Solutions releases two foam AeroSubstrates for hydroponic growers