Crop-damaging insects are difficult enough to manage when growers have a full range of knowledge on how to combat them. Recently, researchers discovered a pair of new and uncommon pests that pose a range of threats to ornamental plants. Growers are now on the lookout for a new thrips species, Thrips parvispinus, as well as a rare mealybug variety, Ferrisia virgata.

Thrips are tiny, elongated insects in the order Thysanoptera – adults have long, feathery wings while immature versions of the insect are wingless. Generally, thrips vary in length from 0.5mm-5mm, ranging in color from completely yellow to yellow with a dark abdomen. A few species are brightly colored – for example, the distinctive reddish-orange larvae of the predatory Franklinothrips orizabensis and F. vespiformis thrips.

Thrips are mainly attracted to flowering plants. With their ability to move long distances in the wind or via infected plants, they are especially troublesome. These slender insects feed by scraping the outer layer of host tissue and sucking out sap and cellular contents. Results of this activity include stippling, silvering or discolored flecking of the leaf surface. Insect infestations are often accompanied by black varnish-like flakes of excrement, known more commonly as frass.

In 2020, a new thrips species was found in Florida on foliage plants. Identified as T. parvispinus (Karny), this was the first report in the continental United States. A native to the Asian tropics, this species has been invading new regions over the past 20 years. Preferring to feed on foliage and tender buds, it has been found on various plant hosts including peppers, papaya, mandevilla/dipladenia, ixora, schefflera, gardenia and anthurium.

University of Florida entomology professor Lance Osborne is front-and-center researching the spread of T. parvispinus, first collected in a central Florida greenhouse by the state’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The 2020 emergence of the insect was followed by its wider proliferation in 2022 on Palm Beach Island, where the pests decimated scores of residential gardenia hedges.

“Florida, first of all, is ground zero for these new and invasive species,” says Osborne. “The joke around here is about finding the bug of the week.”

A high reproduction rate, combined with a preference for hiding in protected areas of a plant, make thrips difficult to control. Studies are currently underway at the University of Florida research centers, although like any new pest, knowing what works best on T. parvispinus will take time. The industry doesn’t yet know enough about their biology, host plant range or what chemicals will work best to control them, Osborne says. “So, we have to guess. When a new invasive species arrives, we can only perform tests on it at ground zero where it’s been found. The greenhouse grower had to spray every few days and wasn’t getting the level of control he wanted, so we don’t know what’s working.”

Biological control was another option explored for controlling this new species of thrips.

“The grower also tried lacewing larvae, one of the most effective predators of thrips, mealybugs, aphids, spider mites, leafhopper nymphs, scales and whiteflies. This method of biological control – using the lacewings as treatment – was too expensive,” Osborne says.

“Trials are currently underway screening insecticides for activity against this pest. During this ongoing learning period, growers must remain educated and stay patient,” says Osborne. “My advice is don’t panic."

Another emerging pest

Like thrips, mealybugs typically enter a greenhouse on infested plant materials, tending to hide along a plant’s veins or in hard-to-detect crevices where branches connect to the main stem. Because of their small size, mealybugs are easily missed by growers until populations build to the point where control becomes more challenging.

The insects use their piercing-sucking mouthparts to draw sap and other fluids from leaf tissue, flower buds and shoot tips. White, waxy tufts on plants are telltale signs of a mealybug infestation, although mealybugs also excrete honeydew that turns into black sooty mold. The mold inhibits photosynthesis in plants, detracting from their appearance and making them harder to sell. Additionally, feeding by adult and nymph mealybugs can cause stunting, leaf yellowing and distortion of plant parts.

Mealybugs are soft-bodied and segmented oval-shaped insects in the Pseudococcidae family. They are attracted to warm, moist environments, making a greenhouse operation a prime target for invasion. There are several species of mealybugs, with the most common being the citrus mealybug (Planococccus citri) and the long-tailed mealybug (Pseudococcus longispinus).

Another mealybug type has been making an appearance in ornamental crops over the last two years; it is known as the striped mealybug (Ferrisia virgata). While the occurrence of the striped mealybug is not new to the U.S., it is not as commonly seen in operations as the madeira mealybug, long-tail mealybug or citrus mealybug. This species has been found on poinsettia, hibiscus and some foliage crops.

Whether a new type of thrips or an uncommon mealybug, the discovery of a new pest is often bad news for growers, says Nancy Rechcigl, technical field manager for ornamentals at Syngenta. “Growers are faced with many challenges every day, but when a new pest comes on the scene, it can be very disruptive to operations,” says Rechcigl. “There are many questions that need to be addressed, such as ‘Can the pest be controlled with current insecticide products?’ ‘What is the life cycle of the pest?’ ‘What plants are susceptible?’ and ‘What is the best way to scout for this pest?’ Pests truly new to the U.S. often come under state regulations, and quarantine requirements may be put in place to help limit the spread to other areas. In these instances, shipping and transport of plant material can be sharply disrupted.”

How to get started

“Consulting a local extension agent can put a grower on the path to species identification,” notes Rechcigl. Agents can advise a grower on where to send insect samples, usually a state lab similar to the University of Florida facility where researchers are currently studying T. parvispinus.

Growers are understandably concerned about shutting down new thrips and mealybug populations before they build to damaging levels. Insecticides registered for the control of mealybugs must be applied early and often, as the white, waxy secretion that covers their bodies will likely necessitate multiple treatments.

“Sprays targeting the immature stage of mealybugs tend to be more successful, since they have less wax on their bodies and are mobile, which means they are exposed to more treated surfaces,” Rechcigl says.

“And when it comes to controlling thrips, the process can be a real challenge due to their small size and cryptic habits,” adds Rechcigl. “They prefer to feed on new, tender growth in terminal buds, flowers, and along the midribs and veins,” she says. “Getting sprays into these areas can be a challenge. Thrips also have a fast lifecycle under warm conditions, so populations can build quickly in a short period of time.”

Mainspring® GNL is a powerful insecticide when used in a proper rotation. Powered by the active ingredient, cyantraniliprole, in IRAC Group 28, this systemic, neonicotinoid alternative shields crops from chewing and sucking insects such as thrips and mealybugs. Applied as a spray or drench, the insecticide works primarily through ingestion. Affected insects stop feeding within minutes, leading to mortality within a few days.

Mainspring GNL prevents pests from establishing and causing extensive crop damage. Drench applications deliver 10-plus weeks of control against established species like Western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis).

“For foliar feeders like T. parvispinus, Mainspring GNL offers the potential for good control as shown in early trials,” says Rechcigl. “The key will be to get the drench on early, once the crop has fully rooted in,” Rechcigl says.

Visit GreenCastOnline.com/MainspringGNL to discover how to shield your crops from damaging pests.

Follow Syngenta on YouTube @SyngentaOrnamentals for the latest product information.

All photos are either the property of Syngenta or are used with permission.

Performance assessments are based upon results or analysis of public information, field observations and/or internal Syngenta evaluations. Trials reflect treatment rates and mixing partners commonly recommended in the marketplace.

© 2023 Syngenta. Important: Always read and follow label instructions. Some products may not be registered for sale or use in all states or counties and/or may have state-specific use requirements. Please check with your local extension service to ensure registration and proper use. GreenCast®, Mainspring® and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. All other trademarks are the property of their respective third-party owners.

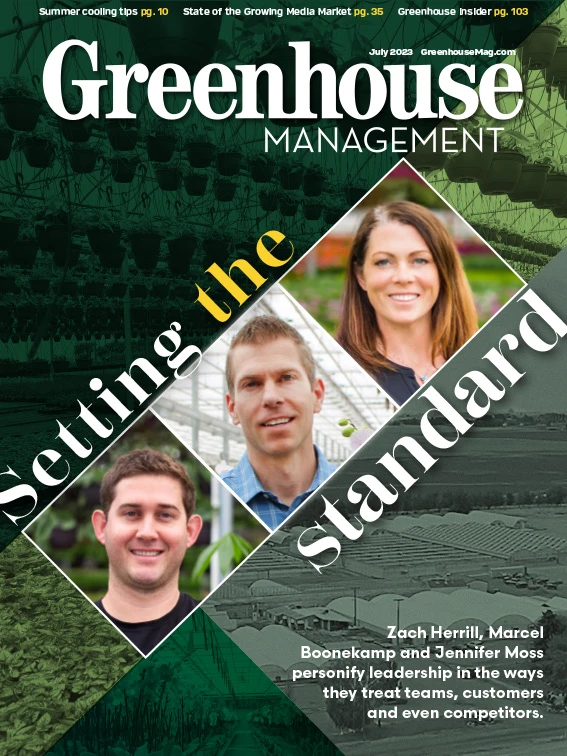

Explore the July 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Produce Grower

- John Bonner focuses on purposeful progress as founder of Great Lakes Growers

- The Growth Industry Episode 1: State of the Horticulture Industry

- FDA to Hold Webinar on Updated ‘Healthy’ Claim

- VIDEO: Growing media for strawberries grown under different production systems

- Eden Green Technology CEO Eddy Badrina reflects on challenges, opportunities for CEA

- Why CEA businesses should track carbon KPIs

- UGA professor Erich Schoeller to discuss IPM best practices for CEA at Indoor Ag-Con 2025

- Jason Jurey from Cropking to discuss CEA in K-12 education at Indoor Ag-Con 2025