For most people, the buzzing of bumblebees provides a low-level, throbbing anxiety. For growers, it should provide high-level excitement.

For most people, the buzzing of bumblebees provides a low-level, throbbing anxiety. For growers, it should provide high-level excitement.

Pollinators can greatly improve the quantity and quality of your yield. Rich Hatfield, an endangered species conservation biologist with the Xerces Society, says that employing pollinators in the greenhouse can increase fruit production on certain plants (tomatoes, peppers) by around three times.

“Without pollinators the plants are forced to self-pollinate, so they’re basically just delivering pollen from one flower to the stigma in the same flower,” he says. “Plants, like humans, try not to reproduce with close relatives. They get a better fruit set when they receive pollen from elsewhere.”

Hatfield adds that cross-pollination is important and without pollinators to move pollen around, particularly in a closed environment (where there is little wind or other natural moving factors), plants are unlikely to develop the best-possible fruit set.

The best species of bee for greenhouse growers tends to be the bumblebee. Honeybees might be more familiar to some growers but they are one of the least effective indoor pollinators. Honeybees, typically, do not work well within enclosed systems, making them less efficient. They are also less effective pollinators for tomatoes because of their inability to extract pollen from the plant.

Bumblebees are able to extract pollen from the tomatoes by fastening their jaws onto the staminal tube and then setting the flower into vibration by activating their flight muscles. Honeybees are unable to match the same vibration frequency and are mostly unable to extract pollen. Employing the use of bumblebees will also eliminate the need for manual pollination, freeing up the grower or their staff to accomplish other tasks.

According to work by Cathy Thomas, the Pennsylvania Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Coordinator for the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, bumblebee colonies are usually shipped in maintenance-free hives. The housing is made of solid, recyclable cardboard with moisture resistant coating. Hives will come equipped with two flight openings.

Bumblebees are most active in the morning and in the afternoon at temperatures between 50 and 86 Fahrenheit. They will function best between temperatures of 59 and 77 Fahrenheit.

Thomas also notes a few factors growers should consider when installing bees:

- Know which pesticides you are employing and their effect on bees.

- Remove blue sticky cards since they may attract bumblebees.

- Once installed, be sure to keep ants away from the hive.

She also says that bees can be used on crops like peppers, cherry tomatoes, eggplants and blueberries.

Native perks

Hatfield also recommends that growers pursue the use of native bees, where possible. For Western U.S. growers, that’s a tricky proposition. Hatfield says that there is not currently a native species available in the West. Eastern-based growers can receive the common eastern bumblebee.

| Research conducted through The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation compared yields in wind-pollinated Sungold cherry tomatoes with Sungold plants pollinated by native bees. Results showed that plants pollinated by native bee vibration yielded a 45-percent increase in fruit set, and the fruit on native-bee-pollinated plants averaged double the weight of fruit on wind-pollinated Sungolds. Researchers attributed extra yields to the efficiency of pollen release achieved by native bees and cross pollination that occurred as bees moved on. – Garden Center Magazine |

As noted by Jolene Hansen in an article for Garden Center magazine, native bees offer adaptations not found in non-native bees. Blueberries, eggplants, tomatoes, and squash are just some of the edibles that native bee pollination pushes to peak performance. Bumblebees, with 50 species native to the U.S., enjoy diverse plants over a long season. Other bees, such as the southeastern blueberry bee, specialize in target plants. Inclement spring weather doesn’t bother these well-adapted bees; it’s par for their native environment. The blueberry bee’s short season of activity coincides with the onset of blueberry blossoms with thick, sticky pollen. Not ones to wait for sunny days, the native bees dive right in.

Hansen further notes that many native bees enjoy the same succession of season-long blooms achieved in thriving edible landscapes that weave edibles in through other ornamental plants. Certain plant qualities encourage diversity in the bees they draw. Long-tongued native bees, perfect for penstemon, gladly dine on echinacea, rudbeckia, and other open-faced flowers that short-tongued native bees need. Many herbs and edible flowers are strong draws for native pollinators. Lavender, culinary sage, thyme, and oregano provide nectar, pollen, and beauty when allowed to bloom.

Synergy between native plants and bees that coevolved alongside them is a winning pollination combination for nearby edibles. Tomatoes produce abundant pollen but no nectar for visiting buzz pollinators. Nectar-producing natives such as monarda, which replenishes nectar quickly, complete the edible equation. Pairing nectar- and pollen-producing native and non-native plants with edibles in your greenhouse creates beautiful, productive gardens.

To protect both the bees within their greenhouse and the bees outside of it, growers should take steps to ensure that all greenhouse screens are closed and the production bumblebees are unable to escape outside.

“Growers should also be sure to use queen excluders and other factors to ensure that commercial bumble bees aren’t escaping into the wild,” Hatfield says.

To maximize the usefulness of the bees, he says, distribute them throughout the greenhouse, ensuring the bees will forage close to their nests. Also, try to apply any insecticides prior to flowering or while the bumblebees are not active.

Hatfield hopes growers can help in the creation of healthier bee species by remembering these four things:

- Commercial bumblebees do not escape from greenhouses by using screens and other protections.

- Colony boxes use queen excluders and that colonies are properly disposed of (not released into the wild).

- They are using a commercial bumble bee species that is within its native range.

- The bumble bees that arrive at their greenhouse facilities are disease free.

Bumblebees also need to be re-stocked every few years. Hannah Burrack, association professor of entomology and an extension specialist at North Carolina State University, says that bumble bees, unlike honeybees, have to re-stocked every few years. She says that honeybees have been raised domestically for much longer than bumblebees, making honeybee colonies easier to maintain.

Bumblebees also need to be re-stocked every few years. Hannah Burrack, association professor of entomology and an extension specialist at North Carolina State University, says that bumble bees, unlike honeybees, have to re-stocked every few years. She says that honeybees have been raised domestically for much longer than bumblebees, making honeybee colonies easier to maintain.

“We know a lot more about honeybees just by virtue of our long association with them,” she says. “We don’t quite know how to keep bumblebees going in quite the same way.”

For more: The Xerces Society’s Pollinator Conservation Resource Center provides regional plant lists, conservation and pesticide resources, nesting and bee identification guides, and edible-related information: www.xerces.org/pollinator-resource-center

| The Garden Center Conference & Expo, presented by Garden Center magazine, is the leading event where garden retailers come together to learn from each other, get inspired and move the industry forward. Be sure to register by April 17 to get the lowest rates for the 2025 show in Kansas City, Missouri, Aug. 5-7.

|

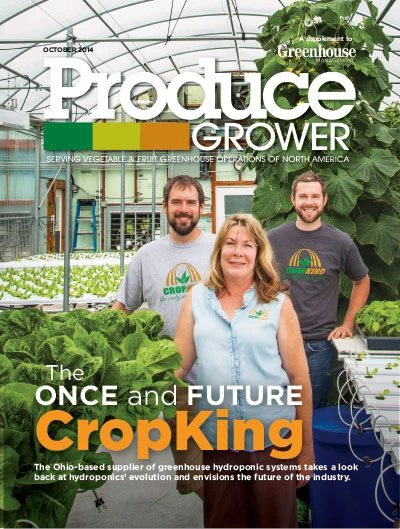

Explore the October 2014 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Produce Grower

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- PG CEA HERB Part 2: Analyzing basil nutrient disorders

- University of Evansville launches 'We Grow Aces!' to tackle food insecurity with anu, eko Solutions

- LettUs Grow, KG Systems partner on Advanced Aeroponics technology

- Find out what's in FMI's Power of Produce 2025 report

- The Growth Industry Episode 2: Emily Showalter on how Willoway Nurseries transformed its business

- 80 Acres Farms expands to Georgia, Texas and Colorado

- How BrightFarms quadrupled capacity in six months